The Kobold Guide to Worldbuilding is out, and we have a special discount code for the ProFantasy community: go to the Kobold Store and use the code CC1PFWB0 at checkout to get 25% off any of the following titles:

- Kobold Guide to Worldbuilding (Print+PDF)

- Complete Kobold Guide to Game Design (Print+PDF)

- Complete Kobold Guide to Game Design (PDF only)

- Kobold Guide to Board Game Design (Print+PDF)

- Kobold Guide to Board Game Design (PDF only)

Below is an excerpt from the Kobold Guide to Worldbuilding: Wolfgang Baur’s essay “How Real is Your World? History and Fantasy as a Spectrum of Design Options.”

Real Worldbuilding

Real Worldbuilding

There are at least two clear traditions in fantasy worldbuilding: the real worlds and the pure fantasies. Fans of the two approaches are usually split and sometimes react violently to the wrong flavor. As with all matters of art and creative endeavor, this is a matter of subjective judgments and personal preferences. The quality of the execution carries a great deal of weight as well.

To put it simply, the competing traditions are these: some fantasy worlds are built more closely on real European legends (such as Conan’s Hyborea, or an Arthurian variant, or Golarion’s many Earthlike cultures), while others are built more clearly on a premise or a conceit (Barsoom or Dark Sun or Spelljammer). A few fall somewhere in between, but let’s pretend for a moment that these are entirely different schools of thought with respect to worldbuilding.

Hard Historical Fantasy

For the historical fantasy settings, I’m thinking of things like Jonathan Tweet’s Ars Magica, Clark Ashton Smith’s Averoigne, Chad Bowser’s Cthulhu Invictus, Sandy Peterson’s Pendragon, Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos and the related RPG, White Wolf ’s World of Darkness, and Scott Bennie’s Testament. These are excellent fantasy worlds, with a specific character, a specific time period, and are built on the firmest ground of realism you can imagine for something that is still clearly a fantasy setting.

This approach is a powerful shortcut to familiarity. It makes these worlds easy to explain to players, and Hollywood uses this formula often as well (“It’s the Wild West—but with UFOs!”). This makes it easy to get buy-in from players or readers, and it simplifies your workload and enriches your storehouse of reference material.

But the style also creates its own limits. Once you are committed to King Arthur and the Round Table, it’s tough to work in Cthulhu (though hardly impossible—Mordred and Morgan Le Fey were clearly cultists!). Once you are discussing wizards and medieval Europe, it’s hard to suddenly bring in wuxia martial arts. A known setting can be bent pretty far, but must never violate the mysterious line where disbelief creeps in. The approach often taken for this sort of design is to declare that the history of the world is well known—but that there is also a secret history, known only to vampires, or Templars, or wizards.

Because this clarity of focus makes the game easy to explain to others (“It’s

the Crusades with magic” or “It’s the Chinese Three Kingdoms with secret Lotus monks”), know in advance that your audience may be small but intensely loyal and likely includes many experts in the period in question.

“Real Fantasy”

Which brings us to the world that is clearly full of the echoes of history and reality, but divorced from it to a greater or lesser degree by its fantasy conceits. It’s one step more fantastical, if you will; its magic is bigger and brighter and its history and sense of earnestness about itself is one step less, while still respecting the roots and traditions of fantasy. There’s more Cthulhu, more fireballs, more giant robots, bigger bets on dragons and monsters and the fantastical coming into the open, rather than the Secret History approach.

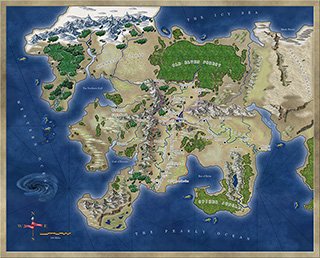

To quote particular examples, I’m thinking of settings like Robert E. Howard’s Hyborea, Jeff Grubb’s Al-Qadim, Suleiman, Kenson, and Marmell’s Hamunapta, my own Midgard campaign setting, Bruce Heard’s Mystara, David “Zeb” Cook’s Kara Tur/Oriental Adventures, Tracy Hickman’s Ravenloft, John Wick’s 7th Sea, Games Workshop’s Warhammer RPG, and Greg Gorden’s TORG. Some of these lean more heavily on the real and some more on the fantasy, but in each case, the designer clearly has a shelf full of real-world reference books. Others, like Roger Zelazny’s Chronicles of Amber, Richard Baker’s Birthright, and Paizo’s Golarion, all lean fairly heavily on Earth and its cultures, so they seem to belong here as well.

Each of these owes a great or lesser debt to the real world’s cultures and societies, and the usual points of departure include the world’s great mythologies and legends, such as the Egyptian mythos, the Norse sagas, the 1001 Arabian Nights, the tales of Stoker and the stories of Atlantis and the Song of Roland, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, pirate tales, the tales of Baron Munchhausen, and the Holy Roman Empire. They’re all built on the assumption that the real world is worth embellishing, and that fantasy is a matter of making real places or real legends more exciting. If dragons were real . . . life would be more exciting.

In each case above, it’s impossible to imagine that fantasy setting without the body of lore that undergirds it. As the designer of such a setting, you must understand what makes that mythology tick, and why it appeals to a modern audience. Once you understand it, your work is to make it both accessible and playable by lifting the best parts of it and making them irresistible to gamers. The more of the obscure points you know, the better off you are.

At the same time, it’s very easy to get trapped in excessive research that players won’t care about, and your prose and descriptive detail can become dry and academic. In a historical fantasy, that’s more acceptable than in a real fantasy, where the goal is not so much “simulation plus a little fantasy” as it is “experience an improved version of the tales.”

That’s right: your goal is to do a better job on the Arabian Nights, to improve on the Brothers Grimm, and to swipe the best bits of ancient Egyptian lore from 5,000 years ago, and make it compelling reading for teenagers, college kids, adults of all ages in the 21st century.

No one said it was easy.