Campaign Cartographer, the Writer / Designer’s Friend

Part 3 – Developing fiction

Outlining a work of fiction is also about moving stuff around. Some writers prefer to hit the page and start writing, and then sort out the structure during subsequent revision rounds. Personally, I need to have the narrative line worked out in some detail before the first draft starts. Minor transitions and obstacles are often stronger if you think them through on the day, but the broad sweep has to be in place. (Outlines are also essential when you’re working with an editor who has to sign off on your story before you start writing in earnest.)

Plotting never gets easy. For me, it typically starts with a few key situations or images. Then I bash around on a scratch document in which I trawl for some kind of unifying spine. During this phase I ask myself the defining questions shaping the story I’m about to assemble. What is this story about, in a single sentence? Who are my characters? What drives them, and to what actions?

Once the answers to those questions have been nailed down, I fire up CC to move from a verbal conception of the narrative to a visual one. Basically I’m taking the known elements of the story and treating them as dots I’ll have to connect. Usually at this point I’ll already have an opening sequence that poses the above questions and impels the protagonist into action. Chances are I’ll also know the twist that changes his or her quest, and also a climax and conclusion. At this stage I now have to conceive the connective scenes that build engagingly toward those moments.

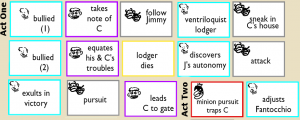

Screenwriters often place their plot points on index cards and move them around on a cork board. CC allows me to move them around on a virtual corkboard that’s as big or small as I want it to be at any time. I can zoom in and zoom out as needed. And I transform the index cards into any kind of graphic element I want

Typically I use blocks of text, coded in some way to tell me which characters are involved in any given scene. This allows me to make sure that all of the characters develop as needed throughout the narrative. If I see that I haven’t got enough action for a major character, I might either create new prospective scenes for him, or realize that he’s not really as important to the story as I thought. I might see that an apparently minor character is cropping up in many of the scenes, warning me to make him interesting enough to hold the reader’s attention for all of that time. I may need to introduce him earlier to suit his new weight in the narrative, leading to an insertion of one or more additional text blocks.

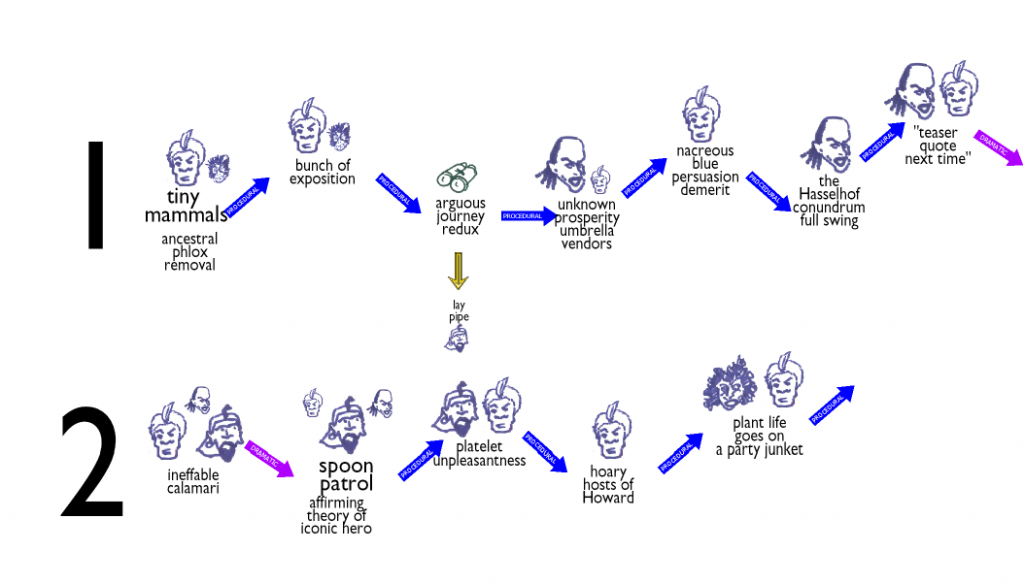

To visually represent characters, I doodle quick cartoony images, scan them in, and convert the resulting PNG file into a CC symbol. This allows me to easily drop the symbol representing each character over each plot point. If your doodling skills are even more primitive than mine, you could cast your characters from images found on the internet, converting them to PNGs if necessary and then to CC symbols.

A look at the diagram so far shows me the gaps I need to fill, if any, in my search for a narrative that is coherent on both the logical and the emotional levels.

To search for logic problems is to test the believability of the story (within whatever genre conventions it establishes.) What practical considerations within the world of the story am I glossing over? I might want Josie to be at the bridge with the bomb, but see that logically Jimbo would have stopped her back at the ranch. Having seen the problem, I have to either find a credible reason for Jimbo to cooperate with my plotting needs—or concede that my story is contrived, and start over with a series of plot points that properly arise from the collisions of the characters’ competing intentions.

Above there’s a detail from a CC fiction outline composed in index card fashion. Each box represents a major story beat. Character symbols identify the driving character in the scene; I’ve also color coded the boxes to the driving characters:

I also want to be able to plot the emotional line of the story. So rather than simply connecting the plot points in a series of boxes, I use up and down arrows to see the shifts in fortune as the hero cycles between adversity and triumph. This approach wouldn’t be needed for certain stories, in which it’s completely appropriate to stick with the same mood for long periods of time. Most narratives, though, genre or otherwise, keep us engaged by varying our hope and fear responses. Here I can see if I need to insert some relief into an otherwise down section, or find additional ways to challenge a protagonist who is having too easy a time of it.

The result can be a very long diagram. It’s unwieldy on the page, but easy to scroll through on the screen. CC allows me to zoom out to see the story’s entire narrative line, beat by beat, or zoom in to fix a problem area in need of revision.

Whenever I spot a scene that needs minor clarification, I can change the text element. If the whole thing needs changing, I can cut it and move the elements around it to fill its spot. Or add a new plot point as logic, inspiration or emotional rhythm require, creating a space for it by moving the adjoining plot points.

Here’s an example. This is a work in progress for a client, so I’ve disguised it by changing the beat labels to nonsense phrases.

Notice that the character symbols are sometimes scaled differently within a scene. Sometimes I’ll want to indicate which characters are dominant in a scene, and which ones are hanging around on its periphery. The easy resizing of symbols allows me to scale the size of my character images with a few key strokes.

Notice that the character symbols are sometimes scaled differently within a scene. Sometimes I’ll want to indicate which characters are dominant in a scene, and which ones are hanging around on its periphery. The easy resizing of symbols allows me to scale the size of my character images with a few key strokes.

I’ve also used layers to create alternate versions of a narrative map, each conveying different information. For a story featuring an ensemble cast, I created a column to the side noting which characters achieved defining victories in each installment of a serial narrative. At a glance I could see which characters weren’t registering strongly enough. I then added or replaced scenes in my outline to balance the contributions of each character to the story.

It may well be that no other author would map their narratives in exactly the same way. The up arrows and character icons might be more help than hindrance to someone else. Other writers might, for example, want to start by importing images of locations, organizing their plotting process geographically. They might want a layer of images keeping track of clues in a mystery story, or marking various ways in which the theme of the story is reinforced throughout.

However, the core idea—of using CC as an infinitely fungible and customizable virtual corkboard—is one that any writer who’s every juggled story elements or drawn a diagram might find useful, if not come to inescapably depend upon.

Back to Part 2 – Moving stuff around >>

I love this article. Thanks, Robin!

Totally concur with the sentiment about the ease of moving things around, but hadn’t thought to use CC3 as a virtual cork board until you mentioned it.

In a recent WotC design I found myself constantly tweaking terrain to make the environment more interesting and dynamic, and was thanking my lucky stars that Profantasy makes that so darn easy. Thanks for the insight on textures–really want to try that now!

An excellent article. Never even considered using it for a fiction outline. 🙂

[…] Continue to Part 3 – Developing fiction >> […]